Film historian Geoffrey Donaldson, after whom the GDI is named, lived most of his life in the Netherlands. But his country of origin was Australia. This article is about his early years.

THE PIN-UP MAN

Geoffrey Donaldson: The Australian years

At the young age of twenty- two, Australian Geoffrey Neville Donaldson was proclaimed “Pin-up man 1952” by fifty female employees of the New York film distribution company Lux – specialized in educational films and European productions. Donaldson lived in Australia and had written to the company requesting documentation and to give his opinions on one thing and another. That led to a mutual correspondence and the women at the office looked forward to the letters from the writer from that faraway country, though they were convinced from his handwriting that he was obviously an “old, frustrated intellectual”. It was only after he had, at their request, sent a photo, that they truly became enthusiastic: “It turned out he was tall, curly-haired, and so good looking.” As Pin-up man of the year, his photo was displayed in the middle of the Lux office bulletin board in New York.

In the same way Donaldson later, from the Netherlands, bombarded an endless number of film companies, actors and directors from home and abroad with requests for information and material. As we now know, he had already done the same in his native Australia. We can at least assume that the Lux company was not the only one he approached. So when he left his native country for good early in 1955 and took the boat to Europe, he left a considerable collection of film books, magazines, photos, publicity material and clippings with his mother, Bessie Isabel Donaldson. She lived in Mayfield near Newcastle, New South Wales, where Geoffrey’s treasures were kept in a bookcase, a large steel cabinet, and a steel filing cabinet. It contained, among other things, more than a thousand original publicity photos. Even at a young age, this collector was not satisfied with the most evident. The fact that his collection contains 88 publicity photos for 46 films of D.W Griffith alone, the great American film pioneer from the silent film era, is proof of that.

Geoffrey Donaldson developed his love for film early on in the cinemas in and around the city of his youth, the mining and port town of Newcastle, on the Australian east coast. On the subject of his early passion for film, he wrote the article ‘Her Jungle Love: not suitable for a boy of ten’, published in Dutch in the book Geoffrey Donaldson, een leven voor de film (GDI, 2013). Around the city lay and lies one of the most important coal mining areas in the world and export of this black gold passed through Newcastle harbour. A Billiton copper smelter and steel mill complete the picture: Donaldson grew up in a working-class city surrounded by heavy industry.

Geoffrey Neville Donaldson was born on 29th November 1929 under what were at the time, adverse family circumstances. His mother Bessie was a single, unmarried mother. As far as is known, Geoffrey never knew who his father was. Bessie herself had not had an easy childhood: her mother Florence Sinclair, Geoffrey’s grandmother, died at the age of 26. It was a terrible drama: she died in hospital while giving birth to her fifth child, after the ambulance had waited for almost an hour for a train that had blocked a railway crossing. Following that, Bessie was raised by her mother’s sisters, her aunts Ellen and Evaline.

So Geoffrey never knew his grandmother, Florence. His grandfather, Andrew Donaldson, who was known as a ‘workman’ and seems to have occasionally also worked as a baker, died when Geoffrey was fourteen. We can assume that the grandson was told all the ins and outs of the overseas adventures of his only remaining relative: early in 1918 Andrew signed up as a volunteer to serve in the Australian army in Europe, where the First World War raged. Earlier, in 1915, Geoffrey’s great grandfather, Henry Sinclair had enlisted for the front in western Europe, where mainly France, Great Britain and later the United States, fought against Germany. But when, on 13th October 1918, Andrew finally arrived by boat in London on his way to war, it was already coming to an end. He became a stretcher bearer and appears to have arrived at the front in France only after hostilities had already ceased. The gruesome struggle, which had also been fought in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, had taken the lives of some 9 million soldiers and 7 million civilians and caused many more injuries. Afterwards, stretcher bearers were probably more indispensable than ever. Andrew Donaldson only returned to Australia in the summer of 1919.

During Geoffrey’s childhood, his mother Bessie lived with the Worthington family in Mayfield, a suburb of Newcastle. In the forties, she had a relationship with the previously divorced master of the house, shift worker Herbert. She never married him, but she did informally go through life under the name, Bessie Worthington. It seems then, that Geoffrey only had a father of sorts figure in his life during his teenage years. Herbert trained his own dogs for the greyhound races, a popular pastime at the time in Australia. The fact that Geoffrey’s mother and foster father were caught by the police for stealing clothes, suggests they were not very well-off.

However, Geoffrey did not let himself be held back by this.

In his last year at the Mayfield East Boys School he came third in the class. At Newcastle Boys High School, languages suited him best. He earned an ‘honour’ in English and had good grades in Latin and French. In 1947 he was selected for the Balmain Teachers’ College in Sydney. The exercise book that he kept for his traineeship at a primary school, already shows signs of the Geoffrey Donaldson who later made a name in the Netherlands as a film researcher: methodical, an eye for detail and meticulously well-kept in terms of both content and design. Furthermore, it also shows how well he could draw.

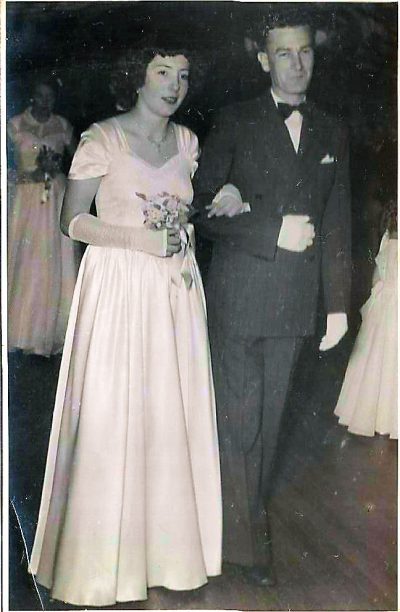

Anyone who graduated from a Teachers’ College in Australia was assigned a position by the government. In 1949, Geoffrey ended up in Comboyne (New South Wales), approximately 175 kilometres north of Newcastle. Comboyne was a small village, an agricultural community, with fewer than 500 inhabitants in 2018, and probably only a few more or a few less back then. It did not have a cinema, only an occasional travelling film screener with old movies passed through. Donaldson became the head teacher and also the sole teacher of the Comboyne East School, which consisted of one classroom for all year groups, adding up to a total of 20 pupils. The highlight of the social calendar in the village was undoubtedly the debutants ball; an annual event when everyone of marriageable age was on their best behaviour.

The only surviving photograph of Donaldson in Comboyne shows the charming young schoolmaster in formal dress with an unknown woman at his side. The education inspector who paid the school a visit, established that he ‘sets a good example in manner, bearing, personal appearance and speech’ and ‘commands the respect of his pupils and the community.’ Meanwhile, Geoffrey had, however, spent many lonely evenings in this remote village. No surprise that letters were sent from this unlikely place to all corners of the world, requesting film documentation: in this way the fire could still be kept burning in an environment where, for as far as the eye could see, there was no cinema.

At the age of about thirteen or fourteen, Geoffrey discovered he nurtured special feelings for men. How was not so grand: in a cinema in Newcastle he was approached by a man who was a total stranger. Going on the graphic description that he later wrote and according to the standards prevailing then and now, if what happened had become known, perhaps the perpetrator would have ended up behind bars. But, as Donaldson says, ‘although I was frightened at first, I knew I had enjoyed the experience.’

It was only years later in Comboyne ‘that I fell in love for the first time. Ted, five years older than me, a dairy farmer, was a very good friend in whose house I lived for a year. We shared a bed, but lay back-to-back alas.’ All of this seems to have escaped Ted. Incidentally, the humble circumstances under which Donaldson lived are immediately clear from this description, something he was probably already familiar with from Newcastle. Later, he was given his own cabin at the school.

At the end of 1954, Geoffrey Donaldson resigned from teaching and soon after left for Europe, never to return to Australia, even though he travelled to many faraway places. In the 24 years after his departure, he did not even see his mother, who died in 1979. What were the underlying reasons for his hasty departure? In the newspapers of the time and in the educational archives, no reason for his departure from Comboyne has yet been found. ‘Resignation accepted as from 31-1-1955’ is all that has been said on the matter. It seems unlikely that it can all be attributed to impulsiveness. Did it become known in the small community of Comboyne that he was homosexual? At that time, that could have been reason enough. In 1950s Australia, there was not much open-mindedness in this area. For this reason, he may have been asked by higher authorities to do the honourable thing, and because of the centralist management of teachers, he would have had very little chance anywhere else. However, given his hasty departure overseas and the apparent break with his mother, perhaps there was more to it than that, in Comboyne or elsewhere. We do not know.

He travelled to Europe on an Italian ship. He wrote that it carried, ‘lots of attractive young Italians returning home to get married.’ We can only imagine what type of remarkable company this could have been. Labourers who had worked in Australia? Liberated prisoners of war from World War II? The ship stopped at Australian ports in places Donaldson had never been before: Melbourne, Adelaide and Fremantle, Perth Harbour, it then probably crossed the Indian Ocean to Colombo in Ceylon (Sri Lanka). The journey continued by way of Aden, the Suez Canal and Port Said. By February 1955 Donaldson was in Italy, probably the last stop of the boat trip. Due to a lack of money, he stayed in youth hostels in Naples and Rome. He thought Rome was a beautiful city, but the Australian Embassy advised him not to stay since unemployment was high. Meanwhile, his stay was once again dominated by film. In Australia, he had seen the film ROMAN HOLIDAY [William Wyler, 1953], he wrote, ‘so I had a good idea of the places and things I wanted to see.’ He beat a path to the doors of film producers and distributors and managed to lay the groundwork for a new collection, with a wonderful gathering of photos and press kits. ‘In both Naples and Rome I was also able to catch up with some Italian films that had not reached Australia before I left, such as L’ORO DI NAPOLI [Vittorio de Sica, 1954] and, particularly and most memorably, SENSO [Luchino Visconti, 1954].’

Little is known of the next phase of Geoffrey Donaldson’s journey. It is likely he continued north by train. Later, he wrote in a letter that he had been corresponding for some years with a Dutch woman, Polly Spree, probably not coincidentally the daughter of an old film actor. He wrote that he hoped to enter into a ‘normal’ marriage with her, but Polly soon realized that he was different and to his great relief plans did not come to fruition. In an interview, Donaldson once said that he was actually on his way to England, where he (also) had a pen pal. In any case he landed in Rotterdam and the Netherlands became his new homeland. That was not without consequences: the film historiography in this country would certainly have looked different without his drive, his precision and his, at times, admonishing contribution.

HANS SCHOOTS

( translated by GERALDINE NESBITT )

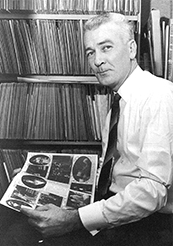

IN MEMORIAM G.N. DONALDSON ( 1929-2002 )

Film historian Geoffrey Neville Donaldson was born in Newcastle, Australia on 29 November 1929. Not much is known about his life in Australia except that, between 1949 and 1954, he was a teacher in the small town of Comboyne East. In 1955, Donaldson decided – unlike the stream of other emigrants – to look for a more adventurous life in Europe.

Donaldson was a collector, and all encyclopaedic research starts, of course, with the collection of facts. In Australia he had already begun collecting pictures and postcards of movie stars and when he arrived in Europe in 1955, one of the places he visited was Rome. The Australian embassy advised him not to look for work there (as unemployment was high). He had more luck with the Roman movie companies that he approached, as he was able to add various press kits and pictures to his collection.

The fact that Donaldson ultimately ended up in the Netherlands was actually by coincidence, since he was supposed to start work as a teacher in England. We owe his life’s work to this coincidence. He had a female pen friend in the Netherlands and he liked it here. For a while, he worked as a tomato picker and as a warehouseman and sales assistant in the Dutch department store, De Bijenkorf. Eventually, he ended up at Unilever, where his command of languages and writing skills were put to good use in the patents department. Later, he moved to Rotterdam to live with Harry van Gunsteren, his life partner and writer for Dutch newspaper Algemeen Dagblad, in their apartment on the Groenendaal, which gradually filled up with movie documentation.

It was probably due to his sexual orientation that Geoffrey Donaldson was particularly partial to the Dutch Diva films that had previously been ignored by Dutch movie writers. One could say even that the rediscovery of the silent Dutch movie may be credited to Donaldson.

Donaldson worked as a translator and correspondent for Unilever and it is interesting to know that he also started his research on movie history as a correspondent. For Donaldson, it was perfectly normal to write a considerable number of letters every day. He must have sent tens of thousands of them in his lifetime. He tried to do as much as possible by post. For example, in his pioneering years, he also corresponded with the Dutch Film Museum that sent him volumes of old movie magazines such as De Film-Wereld (the World of Movies) and De Bioscoop-Courant (The Cinema Newspaper) by registered post. Once Donaldson finished his research on a particular volume, he returned it to the Museum and asked for the next one.

He only left the house to do his research when there was no other way. For example, he interviewed a considerable number of people from the world of Dutch silent movies, including the Netherlands’ first genuine film diva, Annie Bos (1886-1975). Unfortunately, he did not record these interviews, and so Annie’s voice was not saved for posterity. Donaldson liked to write everyone and everything, and built up contacts all over the world. If he felt it was necessary to learn a language for any particular research or contact, he did not hesitate to do so. For example, he taught himself Serbo-Croatian and wrote lengthy letters in that language to friends and people he knew in the movie world of former Yugoslavia.

When Donaldson began to research the history of Dutch silent movies, hardly anything was known about it. The Nederlandsche Filmliga stated in 1933 – through its leader Henrik Scholte – that prior to Joris Ivens’ DE BRUG (1928) Dutch movie art had been practically non-existent:

“We have contributed nothing to the old silent movie. Opportunities, like the ones in Sweden and even in Czechoslovakia, were passed on. We focussed on pretentious five-masters, which were made ready for sailing by impresarios rather than by movie directors, but which already sank in the inland waterways of our national borders and never reached the open seas of the international market.’ (H. Scholte, Nederlandsche Filmkunst, Rotterdam, 1933, p. 8)

Donaldson made it his life’s work to prove Scholte wrong and the weighty book that he eventually published in 1997 did just that.

His publishing activities are probably too extensive to even investigate. In the fifties and sixties, he frequently visited the Berlin Film Festival and wrote about it in the British magazine Films and Filming. Later, he would also publish on movie-historic subjects in the same magazine, as well as in The Silent Picture and Films in Review. In the Netherlands, Donaldson would write mainly for the initially Marxist-Leninist and later more film-theoretically oriented magazine Skrien. The magazine’s various outlooks did not preclude a considerable interest in movie history and Donaldson consequently became an esteemed contributor. His first article for Skrien, in 1970, was programmatically entitled ‘The Dutch silent move and Dutch “movie historians”’ and contained a long list of all the errors that Dutch film writers such as Charles Boost, Emile Brumsteede, Simon van Collem and Ab Ieperen had permitted themselves at the expense of the Dutch silent movie up to then. It would certainly not be the last time Donaldson displayed his critical side.

In 1982, Donaldson became a full-time contributor for Skrien. In his series ‘Who’s Who in Dutch movies up to 1930’ he contributed biographical essays to each issue, completed with filmographies of people who played a more or less important role in early Dutch movie history. The series would run until 1988. With his scientific clarity, but moreover with beautifully written articles, he managed to put the spotlight again on forgotten movie stars such as the Chilean Adelqui Migliar and the Dutch Mimi Boesnach. Using his un-Dutch charm, he asked the readers of Skrien to contact him with additions and/or corrections. Given the numerous epilogues, this happened frequently. He was always willing to admit his own mistakes. For example, he wrote in Skrien 139 that ‘when compiling the filmography of Margit Barnay, I made an incomprehensible, unforgivable but fortunately not irreparable mistake. I forgot to consult volume VII of Gerard Lamprecht’s reference book Deutsche Stummfilme, thus leaving out no fewer than fourteen titles from her filmography”. Which was followed, of course, by an extensive supplement. In addition to his painstakingly accurate research, he always had an eye for the absurdity and often frequent drollery of Dutch movie history. The fable that Donaldson was merely a facts freak who could not write can be reputed by the following quotation from his article ‘Dogs in Dutch Movies’:

“The following – and as far as I know, last – Dutch silent movie in which a dog is directly involved in the plot is entitled WEERGEVONDEN (RETRIEVED), a movie directed by H. Chrispijn for the Filmfabriek ‘Hollandia’ in 1914. Fortunately, this movie was saved, but the original interim titles were missing from the copy that the Dutch Film Museum managed to preserve in 1976-1977, so that the name of the cheeky white keeshond who acted in it could not be found. For the sake of convenience, I will call him ‘Keesie’ here. The preserved copy of WEERGEVONDEN was shown during the 1977 International Film Week in Arnhem. These showings allowed the audience to form an opinion on ‘Keesie’s’ performance. Unfortunately, it became clear that the poorly trained ‘Keesie’ could never have gone up for a doggy Oscar, as he showed little interest in the movie action, but rather focussed his attention on the camera and the people standing behind. He certainly could not resist the urge to look straight into the camera.” (Skrien 122, pp. 12-13)

After he retired from Unilever in late 1989, he was able to focus all his energy on his voluminous book. The Film Museum helped him to do so by giving him a personal computer and lending out a trainee, so that the comprehensive filmography data could also become available in digital form. The work on both sides (Donaldson submitted his information, the Film Museum checked all its own sources and completed the filmography information where necessary, after which Donaldson checked everything again) resulted in Of Joy and Sorrow (1997) a verbal, if not visual pinnacle of Donaldson’s lifelong passion for the Dutch silent movie. Not only did the book offer an impressive overview of everything that had been created in the first 35 years of Dutch movie history, it also contained a wealth of information about foreign releases. For example, the ‘five-master’ EEN CARMEN VAN HET NOORDEN [A Carmen of the North] (Maurits Binger/Hans Nesna, 1919) was shown in the United States in May of that year and in Argentina the following month (Of Joy and Sorrow, p. 184). Filmliga founder Henrik Scholte, who passed away a few years before, received a verbal but especially visual retort.

In fact, Donaldson was not only active in the field of the Dutch silent movie, he compiled, among other things, a pioneering first overview of movies made in the Netherlands during the Second World War. For example, for the famous Lexikon zum deutschsprachigen Film compiled by CineGraph he carried out research into which German actors or technicians had worked on Dutch movies. His work is also included in the Biographic Dictionary of the Netherlands. Donaldson kept an incredible biographic archive of almost everyone who had anything to do with Dutch movies. Many younger fellow researchers consequently visited him at home to consult his famous files. This often resulted in years of correspondence and an ongoing exchange of information. Donaldson was basically a very modest, even shy man who you only really got to know in his letters. In a typical letter sent after one of these afternoon visits, he apologised that he had forgotten to offer his visitor something to drink or otherwise, engrossed as he had been in either the conversation or looking up material from the archive.

I got to know Geoffrey personally in 1988 just after I started my job at the Film Museum and found three previously unviewed film canisters that contained three acts from a Hollandia movie that had been considered lost until then. My correspondence with Donaldson allowed me to conclude that they were acts 2, 4 and the final act 5 from the Annie Bos movie GOUDEN KETENEN [Gold Chains] (Directed by Maurits Binger, 1917). It was my first encounter with the Dutch silent movie and it opened up a whole new world for me. Later, I was able to use his wonderful personal files for my own research into the Dutch movie industry of the forties. Donaldson shared my interest in the forties. He had a comprehensive collection of publicity material on people such as Veit Harlan, Kristina Söderbaum and others. He readily made his material on Jan Teunissen (including the remainder of Teunissen’s archive that had been given to Donaldson after the former’s death in 1975) available to me for my biographical research on this ‘film tsar’. I was able to take the files with the original letters and the collected film scripts of the movies Teunissen edited in the thirties home with me until the research was finished.

Donaldson’s impressive collection contained, among other things, four or five bulky files in which Donaldson saved everything he could find about the countless adventure stories by his favourite author Henry Rider Haggard. This would lend itself perfectly for a proper source publication, as would the impressive collection of material that Donaldson collected about the movies of D.W. Griffith. Geoffrey only showed you those things if you were interested. Let us hope that the Film Museum will make an inventory of Donaldson’s sizeable collection soon so that researchers will not have to do without this Fundgrube much longer.

Dutch State Secretary Rick van der Ploeg awarding Geoff his Golden Calf for his life’s work, Utrecht, 1998.

Donaldson was awarded the 1981 NBF Cinemagiaprijs for his work in the field of movie history and received a special Gouden Kalf during the 1998 Dutch Film Festival for his beautiful book and his pioneering work in the field of Dutch movie historiography. On 9 May 2002 at age 72, he passed away in his beloved Rotterdam. I am sure that I am not the only one who will miss his passion, his critical viewpoint, and, more than that, his friendship.

EGBERT BARTEN

Published in Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis, 2002-2, pp. 143-149

Translated by Willem Smit (Doublespeak translations)